“旱”何以成“灾”—1932−1953年河西走廊西部“旱灾”表述研究

Why Drought Become Disaster

-

摘要: 气候干燥少雨的河西走廊西部是中国西北边疆的重要灌溉农业区。民国中后期至中华人民共和国初期,该区域为解决近代水利危机而开启了水利现代化的历程,同时大量有关“旱灾”的表述频见于各类文献中。分析河西走廊西部主要河流水文特性与耕作制度会发现,“旱灾”与其说是一种真正的自然灾害,不如说是中国西北边疆水利现代化历程中一种独特的政治话语。民国时期,“旱灾”表述被用于社会各界争夺水权、赈济与工程投资的博弈中,地方政府与民众普遍通过以受灾者自居,通过竞相“示弱”争取上级政府的支持,而实际损害更大的水灾则往往遭到忽视。在中华人民共和国初期,政府通过主动发布河流来水可能偏少的“旱灾预警”;在一种“应急体制”的推行与固化中,政府实现了对灌溉活动的绝对控制。国家与社会借“旱灾”实现互动,既体现了西北边疆社会现代化进程中包含的危机性以及对国家的高度依赖,亦表现出“水”作为干旱区的先决性资源始终是国家控制边疆社会的重要政治抓手,并未因社会发生某种“现代化”转型而动摇。河西走廊西部的水利现代化历程以及作为其重要组成部分的“旱灾”话语,也因此具有了独特的“边疆”烙印。Abstract: Climatically arid and with little rainfall, the western part of Hexi Corridor is a major irrigation farming region of China’s northwestern frontier. From mid to late Republican Period up to the early years of the People’s Republic of China, this region initiated the modernization of irrigation in the process of solving irrigation crises in modernity. At the same time, " drought”, as a terminology in discourse, began to appear frequently in various textual accounts. Through analyzing hydrological features of major rivers and farming systems in the western part of Hexi Corridor, this paper points out that rather than denoting a natural disaster, " drought” was born out of a unique political discourse in the modernization of irrigation on China’s northwestern frontier. In the Republican Period, " drought” was used as a discourse in the contest for water right, relief aid, and engineering investment among competing social sectors, so that the local government and its people could portray themselves as victims, in order to win over the endorsement of those in government at a higher level through " a demonstration of weakness”. Whereas flooding, as an actual disaster that was much more damaging, was often ignored. In the early years of the People’s Republic of China, the government proactively released " drought alerts” to gain absolute control over irrigation activities through the promotion and reification of an " emergency response system”. Interaction between the state and society was realized through " drought”, revealing the crisis-nature embodied in the modernization process of northwestern frontier society and its heavy reliance on the state, as well as demonstrating that " water”, as the prerequisite resource in an arid region, will forever serve as a crucial political means for the state to control frontier societies, unshakable by any process of " modernization”.

-

Key words:

- western part of Hexi Corridor /

- drought /

- political discourse /

- modernization of irrigation /

- frontier

-

表 1 讨赖河流域农作物耕种节令调查表①

农作类别 泡地用水

(时令、日期)播种时期

(时令、日期)灌溉时期

(时令、日期)收获时期

(时令、日期)备注 夏禾 小麦 处暑−白露 8.20−9.8 惊蛰−春分 3.1−3.20 立夏−夏至 6.5−6.20 大暑−立秋 7.20−8.10 若浇水不足三次,则不用泡地,秋禾后犁耙,明春种麦,泡间歇地用水须在六月内。 青稞 处暑−白露 8.20−9.8 惊蛰−春分 3.10−3.20 谷雨−芒种 4.20−6.6 小暑−大暑 7.1−7.20 豆类 白露−秋分 9.10−9.23 清明−谷雨 4.6−4.20 小满−立夏 5.20−6.21 小暑−大暑 7.7−7.20 马营、丰乐、洪水三河灌区因水来迟,诸时略晚。 秋禾 糜子 寒露−霜降 10.8−10.23 小满−芒种 5.20−6.30 小暑−处暑 7.1−8.20 白露−秋分 9.1−9.20 较讨赖等河迟。 谷子 寒露−霜降 10.8−10.23 谷雨−立夏 4.15−4.30 芒种−大暑 6.1−7.15 寒露−霜降 10.11−0.10 迟收半月至廿天。 胡麻 白露−秋分 9.8−9.20 清明−谷雨 4.1−4.15 小满−小暑 5.20−7.1 立夏−处暑 8.1−8.20 马铃薯 霜降−立冬 10.23−11.8 清明−谷雨 10.23−11.8 小满−处暑 5.20−8.20 秋分−寒露 9.20−10.8 表 2 河西走廊西部主要河流月平均流量(m3/s)及其年际间的标准偏差

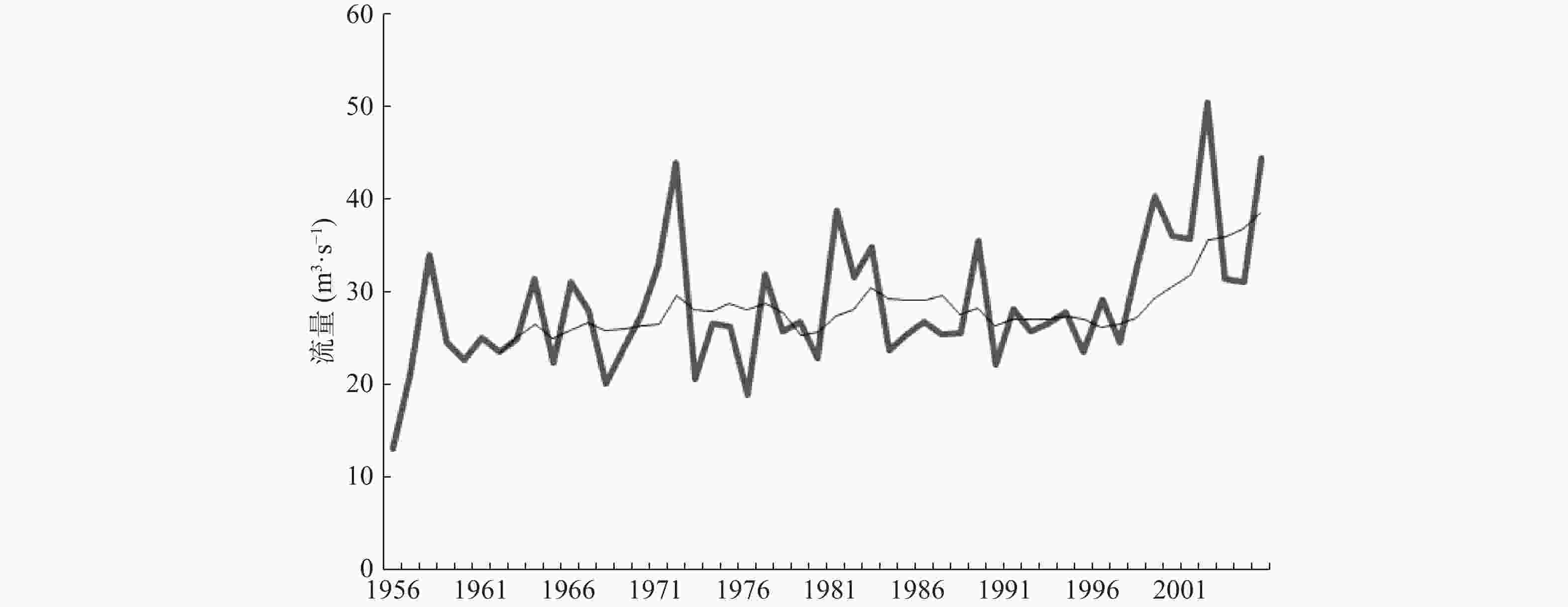

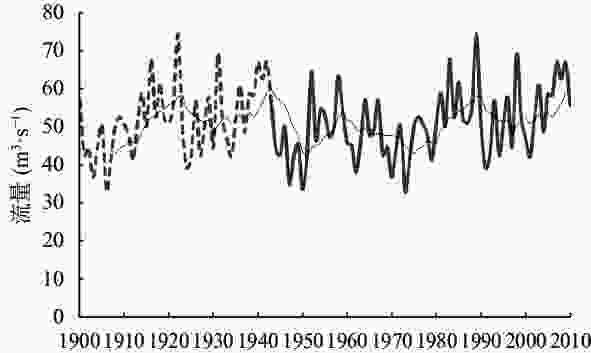

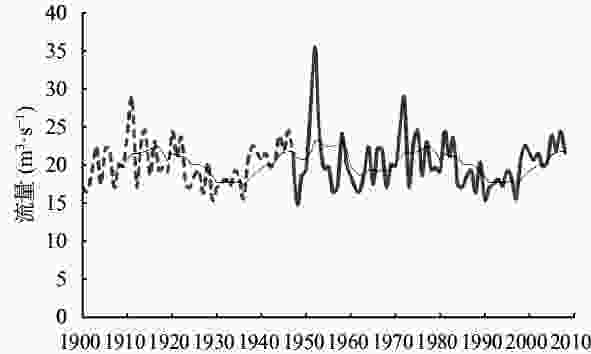

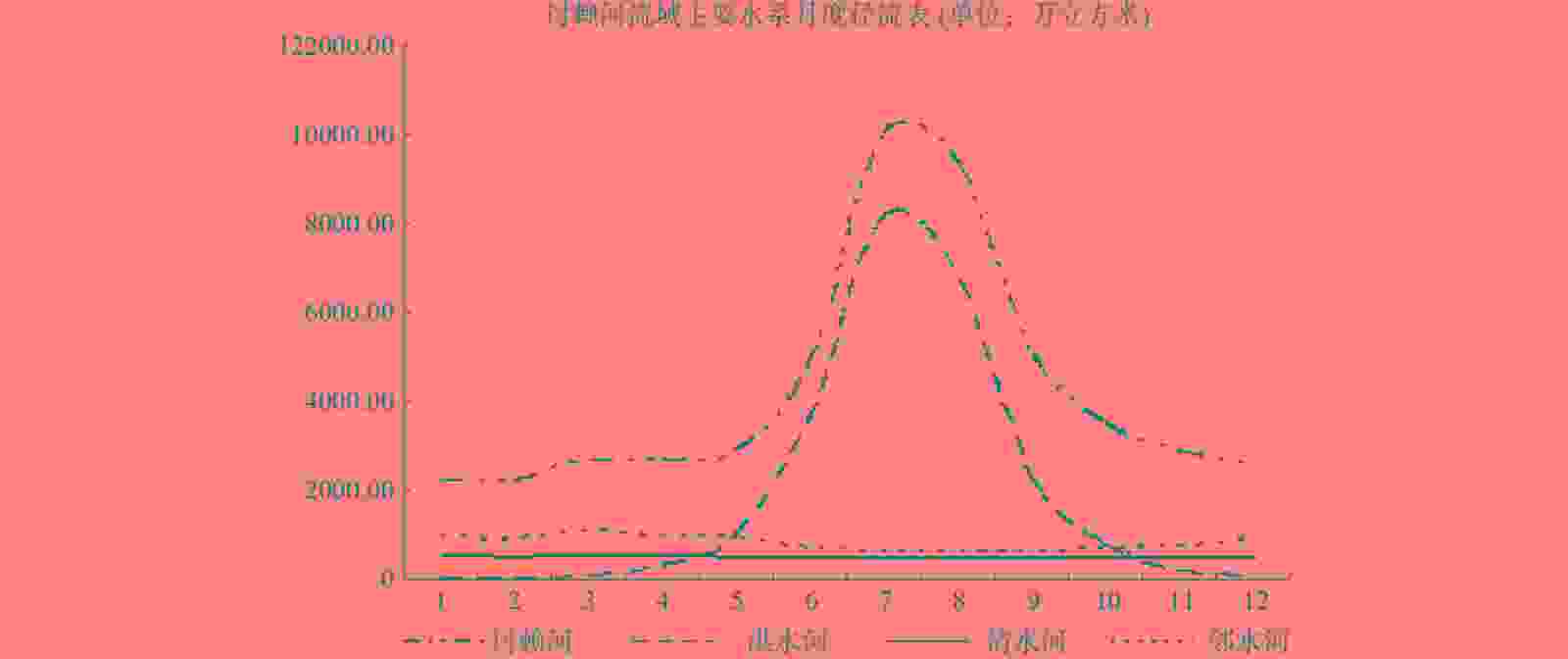

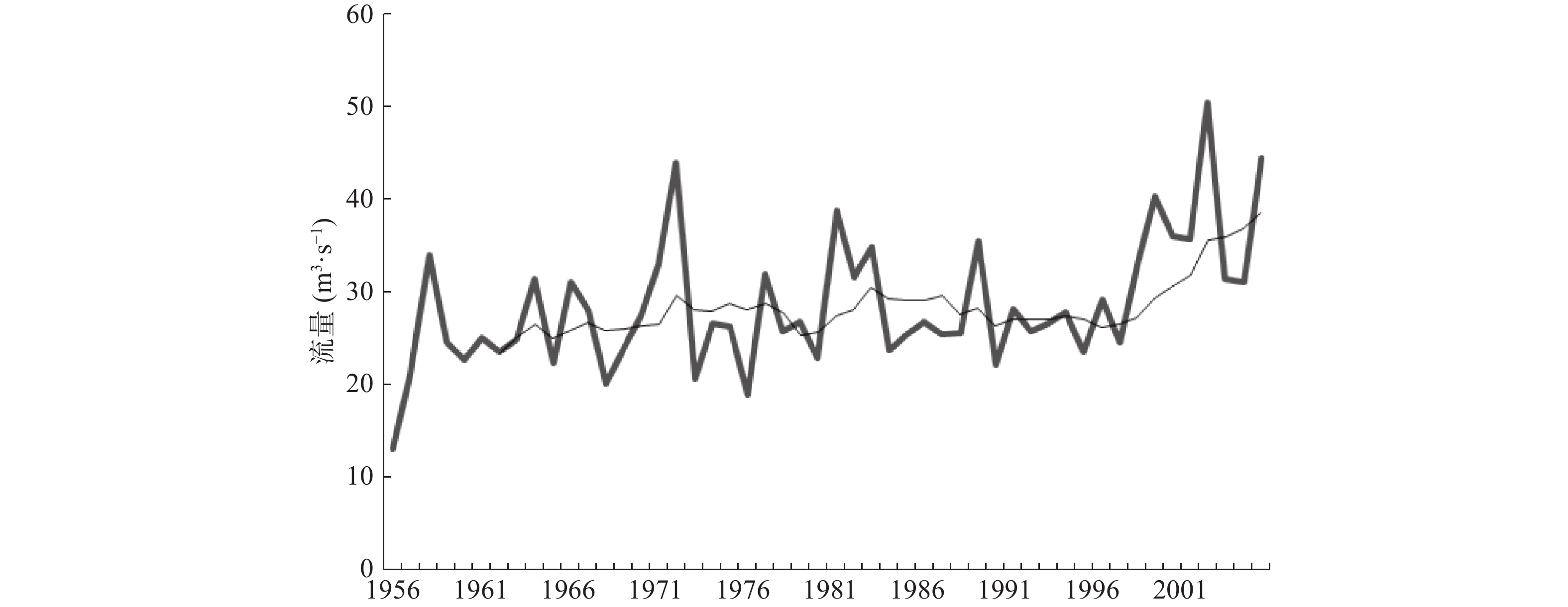

1月 2月 3月 4月 5月 6月 7月 8月 9月 10月 11月 12月 全年 黑河(1944−2010) 平均流量 12.02 11.90 16.14 26.86 44.00 78.45 134.35 118.52 86.76 43.28 24.26 14.21 50.54 标准偏差 5.72 5.74 7.09 5.94 14.86 27.97 39.27 32.37 30.56 13.80 5.62 6.46 8.92 讨赖河(1948−2008) 平均流量 11.98 12.66 12.75 13.78 14.62 21.43 44.99 42.78 25.17 17.21 14.10 12.75 20.35 标准偏差 1.53 1.73 1.70 1.94 2.69 6.24 20.68 15.15 8.35 3.24 1.97 1.42 3.58 疏勒河(1956−2005) 平均流量 9.11 9.67 9.70 16.57 22.31 36.93 82.08 82.44 34.04 17.25 12.99 9.46 28.55 标准偏差 2.51 2.89 2.25 4.10 5.77 12.13 28.51 33.78 14.87 4.37 3.28 2.89 7.03 -

下载:

下载:

沪公网安备 31010102003103号

沪公网安备 31010102003103号